by Brooke Chilvers

There's room for only one hunter in a woman’s life. After a marriage filled with sidelocks and boxlocks, side-by-sides and over-and- unders, the .375 H&H and the .500 Jeffery, if I were someday tossed away or widowed my personal ad would read: “Seeking poet, sailor or angler, with wine cellar. No hunters need apply.”

Then I spent an afternoon with British sporting artist Rodger McPhail’s book, Fishing Season: An Artist’s Fishing Year, and pictured the tackle room that might accompany an angler’s life: racks of rods and shelves of reels; big double-handers for February salmon “fresh up from the tide,” and lighter ones for the thinner salmon rivers of summer; kit for brown trout during the Mayfly and stillwater seasons; saltwater rigs for North-Sea cod and sun-drenched bonefish; heavy spinning gear for pike and light limber rods for carp; big sticks for marlin, sailfish and tuna; wiggling gummy worms for coarse fish; lures, hooks, a zillion flies.

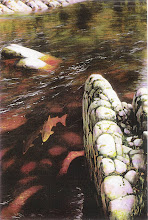

McPhail’s kaleidoscope of images explores every aspect of the angling life and then goes a step further to include all the non-aquatic players, from kingfishers to cows. Even more rare in outdoor art, identifiable (but also anonymous) sportsmen are as much a part of his fishes’ environments as river stones and swaying algae. In fact, McPhail could almost be the Norman Rockwell of angling art, with characters untangling line, snoozing and extracting hooks from their noses.

But these busy pastiches contrast sharply with his silent underwater world, where he captures the unseen lives of fishes as they go about their lives with noble indifference, moving over shoals, swimming through waters streaked with sunlight—or being gutted for the grill.

Summing up McPhail’s angling art, James Babb, who some years ago tried unsuccessfully to bring in a U.S. edition of Fishing Season, wrote that, “McPhail captures not just the beauty but the magic and the mirth of this most senseless yet engaging of all sports, from landing a great salmon in the Highlands to hurling a lunch over the rail off the Lizard.”

It’s interesting to compare McPhail’s sporting art to the wildlife artists who aim their brushes at big-game hunters. Are hunters so distracted by horns and antlers that they don’t notice the birdlife and the bugs that anglers seem to see? Is it because anglers don’t know in advance the size of their catch that they seem to appreciate the subtleties of scenic plumage? Thumbing through the 160 pages of McPhail’s album made the canvases of elk and Cape buffalo at sporting shows seem as lonely as a hunter facing a charge. McPhail’s sportsmen, with only a picnic basket or birdsong for company, immerse themselves deeply in their surroundings.

McPhail says, “Paintings should speak for themselves,” and his actually do. Their voices in his three sporting art books reflect a man who embraces with equal gusto the natural world and the many activities of the British-born sportsman’s life. Googling McPhail is like tracking Hurricane Rodger: He is a deer stalker, wildfowler, angler, artist; an obvious bon vivant who has traveled from the British Isles to America and Africa, along the way illustrating a shelf full of books. He has donated numerous paintings to conservation causes, created posters for gift shops in Kenya and dozens of cartoons that really make you laugh.

Born in 1953 in Lancashire, McPhail began his remarkable career at only 16, illustrating articles, then covers, for Shooting Times, and later for such prestigious publications as The Field, Country Life and Country Illustrated. His first commission, accompanying and painting a partridge shoot in Spain, led to numerous others of the most famous hunts on the biggest estates.

According to British nature writer Ian Alcock, McPhail generally starts with a small sketch of his concept, then on “layout paper” he begins drawing the different elements— fauna, flora, people, boats, buildings; then he places them in relation to each other until he gets the composition just right before tracing them on stretched Saunders hot-pressed paper (for watercolors). Protecting them with masking fluid, he then paints in the background. He follows pretty much the same sequence with his oils done on gessotreated board or canvas, underpainted in acrylic.

McPhail works often in sepiacolored drawings, but even his watercolor palette is very limited— often only four to five translucent colors topped off with opaque highlights. For oils, he may use twice as many colors.

McPhail isn’t a photorealist. And although some of his “lit” images are among my favorite (a wildfowler gathering up his decoys just before dark), he’s generally more interested in conveying the story than in portraying clever light sources.

An Artist’s Fishing Year starts with spring: kelts on the Tweed, trout on the clear chalk streams and snipefilled water meadows of Wessex, fresh-run salmon on the Frome. Sharing the riverbanks are intently fishing herons and mergansers. Primrose and gorse bloom; lambs bleat; swallows and songbirds nest.

Underwater, coarse fish and grayling are ready to spawn, and perch and stickleback deposit their eggs on the riverbottom. At sea, cod and pollock shoal accompanied by puffins and swirling terns. In gin-clear waters, a trout appears between the branches of overhanging flowering brambles—a rare juxtaposition of flora and fisha à la Audubon. In summer, the pace picks up with hungrier fish eyeing hooks everywhere. Along the coast, fishermen dig bait in the low-tide mud flats for dogfish. The rushing rivers of the north enjoy steady runs of salmon and grilse, while the shallowing waters of summer ponds turn opaque with algae. Loons, oystercatchers and plovers highlight the scenery, while night-fishing for sea trout belongs to the moon, bats and owls. And the beer.

Then it’s autumn, and nature is peaking with fattened gamebirds and ripe berries. In rivers and lakes, brown trout come to the well-presented dry. Grayling, the “lady of the stream,” is now at its best, eagerly taking wet flies and nymphs. The water is murky with abundance, its color changing with the sun.

There’s trolling for perch and pike, or looking for bream in the deep waters of sluggish rivers and canals. Salmon fishing peaks as the red deer rut, and the voices of hounds resound in the woods. Carp fishermen sit in quiet night vigil on the ponds. Some sportsmen break from the waters to shoot pheasant and grouse. Then the swallows and geese are almost gone, the water turns cold and then colder, and a wet day of sport ends in the pub.

In McPhail’s fishing year, winter means heading for warmer waters and sailfish, barracuda, tuna. The angling artist takes himself diving, then goes to Africa for Nile perch and tigerfish, casting his line between hippos and crocs. Marabou storks, bee-eaters, and fish eagles, with their unforgettable cries, are never far from the rod.

At home, grayling can still be found on the northern rivers. Hungry pike take anything—plugs, lures, spinners, an unwary duck. Although the fishermen are mostly at home now, whisky at hand, their outings are graced by loyal winter friends—the chickadees and sparrows.

In his art, McPhail conveys the message that sportsmen will never be the cause of the degradation of nature, which in Great Britain remains so remarkably intact. He covers a huge amount of territory in this vast collection of works, painting a lobster with the same care and inspiration as a salmon breaking water. You just know McPhail himself is as happy to catch a lamprey as a salmon. He is the polar opposite of artists forever stuck doing big cats. His sportsmen, indeed, do see the butterflies.

Emerging from these images as from a dream, I read the words, “There are small nymphs and longshanked sea trout lures, tandem flies and small double hooked trout flies, and a range of salmon flies… in a variety of colours and sizes,” and I pitied the wife of the angler who ties his own, forever condemned to breathe and sweep a sea of feathers. Now I understood the presence in McPhail’s winter pages of golden pheasant, jays and partridge, guineafowl, turkey, peacocks and a redheaded boy.

Even considering his lifelong collection of every caliber and old box of ammunition that covers desk, I think I’ll keep my hunter

A fan of grouse in the field, in the pot—or Famous and in the bottle— Brooke says her esteem for McPhail’s work only increased when she learned that he’d done the artwork for the label of Famous Grouse Scotch Whisky.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Angling the Year-round with Rodger McPhail

From the banks of the Tweed to the deep-blue sea.